Christian Symbolism Hand and Finger Gestures in Religious Art

The Mitt of God, or Manus Dei in Latin, also known as Dextera domini/dei (the "right mitt of God"), is a motif in Jewish and Christian fine art, especially of the Late Antiquarian and Early Medieval periods, when depiction of Yahweh or God the Begetter as a full human figure was considered unacceptable. The hand, sometimes including a portion of an arm, or ending well-nigh the wrist, is used to indicate the intervention in or approving of affairs on Globe by God, and sometimes as a subject in itself. Information technology is an artistic metaphor that is by and large not intended to indicate that a hand was physically present or seen at any subject depicted. The Hand is seen appearing from above in a fairly restricted number of narrative contexts, often in a blessing gesture (in Christian examples), but sometimes performing an activity. In later Christian works it tends to exist replaced by a fully realized effigy of God the Father, whose depiction had become adequate in Western Christianity, although not in Eastern Orthodox or Jewish art.[1] Though the paw of God has traditionally been understood as a symbol for God'due south intervention or blessing of man affairs, information technology is also possible that the mitt of God reflects the anthropomorphic conceptions of the deity that may take persisted in late antiquity.[2]

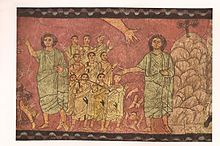

The largest group of Jewish imagery from the ancient world, the 3rd century synagogue at Dura-Europas, has the hand of God in five different scenes, including the Sacrifice of Isaac,[iii] and no doubt this was one of the many iconographic features taken over by Christian art from what seems to take been a vigorous tradition of Jewish narrative art. Here and elsewhere it often represents the bathroom Kol (literally "daughter of a voice") or voice of God,[a] a employ too taken over into Christian art.

The hand may also chronicle to older traditions in various other religions in the Aboriginal Near East.[iv] In the fine art of the Amarna menstruation in Egypt under Akhenaten, the rays of the Aten sun-disk cease in small easily to propose the bounty of the supreme deity. Like the hamsa amulet, the hand is sometimes shown lonely on buildings, although information technology does not seem to have existed as a portable amulet-blazon object in Christian use. It is constitute from the fourth century on in the Catacombs of Rome, including paintings of Moses receiving the Law and the Sacrifice of Isaac.[5]

There are numerous references to the hand, or arm, of God in the Hebrew Bible, virtually clearly metaphorical in the way that remains electric current in modern English, only some capable of a literal interpretation.[1] They are unremarkably distinguished from references to a placement at the right paw of God. Later rabbinic literature also contains a number of references. At that place are three occasions in the gospels when the voice of God is heard, and the hand frequently represents this in visual art.[6] Gertrud Schiller distinguishes 3 functions of the mitt in Christian art: as symbol of either God's presence or the vocalization of God, or signifying God's acceptance of a sacrifice.[seven]

In sacred texts and commentary [edit]

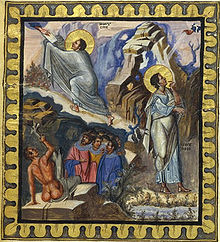

The Hand of God intervenes at the Sacrifice of Isaac, Armenian, Akdamar, 10th century

Hebrew Bible [edit]

The hand of God, which encompasses God'southward arm and fingers every bit well, is one of the most often employed anthropomorphisms of the Hebrew Bible. References to the hand of God occur numerous times in the Pentateuch alone, peculiarly in regards to the unfolding narrative of the Israelites' exodus from Egypt (cf. Exodus iii:19–twenty, Exodus 14: 3, 8, 31).[8]

New Testament [edit]

There are no references to the hand of God as an active agent or witness in the New Testament, though there are several to Jesus standing or sitting by the right hand of God in God's heavenly court,[9] a conventional term for the place of honour beside a host or senior family unit member. For example, when Stephen is filled with the "holy spirit" he looks to heaven and sees Jesus standing past the correct manus of God (Acts seven:55). There are three occasions in the Gospels when the voice of God is heard, and the hand of God often represents this in visual art.[10]

Rabbinic literature [edit]

Anthropomorphic aggadot regarding the manus of God appear frequently in the corpus of rabbinic literature and aggrandize upon anthropomorphic biblical narratives.

Christian art [edit]

In Christian fine art, the hand of God has traditionally been understood as an artistic metaphor that is not intended to indicate that the deity was physically present or seen in any field of study depicted. In the late antique and early medieval periods, the representation of the concentrated figure of God the Male parent would accept been considered a grave violation of the 2d Commandment.[11] According to conventional art historical interpretation, the representation of the hand of God in early on Christian fine art thus developed every bit a necessary and symbolic compromise to the highly anti-anthropomorphic tenor of the Second Commandment, though anthropomorphic interpretations are certainly plausible.[12] In early Christian and Byzantine art, the paw of God is seen appearing from above in a fairly restricted number of narrative contexts, often in a approving gesture, but sometimes performing an action. Gertrud Schiller distinguishes three functions of the hand in Christian art: as symbol of either God'south presence or the voice of God, or signifying God'southward acceptance of a cede.[thirteen] In subsequently Christian works information technology tends to exist replaced past a fully realized effigy of God the Male parent, whose depiction had become acceptable in Western Christianity, although non in Eastern Orthodox or Jewish art.[one]

Iconography [edit]

The motif of the hand, with no trunk attached, provides a trouble for the artist in how to stop it. In Christian narrative images the hand most often emerges from a small cloud, at or almost the top of the image, but in iconic contexts it may appear cutting off in the picture space, or jump from a border, or a victor's wreath (left). A cloud is mentioned as the source of the vocalisation of God in the gospel accounts of the Transfiguration of Jesus (encounter below). Several of the examples in the Dura Europos synagogue (see below) prove a expert part of the forearm as well as the hand, which is not establish in surviving Christian examples, and near show an open up palm, sometimes with the fingers spread out. Subsequently examples in Jewish art are closer in form to Christian styles.

In Christian art, the manus of God usually occupies the grade of a blessing gesture, if they are not performing an activeness, though some just show an open up hand. The normal approval gesture is to point with the index and adjacent finger, with the other fingers curled back and thumb relaxed. At that place is likewise a more complicated Byzantine gesture that attempts to represent the Greek letter of the alphabet chi, Christ's initial, which looks similar a Latin letter "X". This is formed by crossing the thumb and little finger inside the palm, with simply the forefinger and next one extended,[14] or a variant of this.

Peculiarly in Roman mosaics, but also in some High german purple commissions, for example on the Lothair Cross, the hand is clenched around a wreath that goes upwards, and behind which the arm then disappears, forming a tidy circular motif. Especially in these examples, the paw may prove the sleeve of a garment, sometimes of two layers, as at San Clemente, Rome. In blessing forms the hand often has a halo, which too may provide a user-friendly termination point. This may or may not be a cruciform halo, indicating the divinity, and specifically the Logos, or Pre-existing Christ (encounter beneath).

The paw is regularly seen in depictions of certain scenes, though information technology may occur on occasion in a much wider range.[15] In many scenes ane or more than angels, interim as the messengers of God, may appear instead of the manus. A nigh unique mosaic depiction of the Ark of the Covenant (806) at Germigny-des-Prés, besides features the hand of God.

In Christian fine art the manus will often actually represent the hand of God the Son, or the Logos; this is demonstrated when afterward depictions commencement to substitute for the Hand a small half-length portrait of Christ as Logos in a similar circular frame. Information technology is almost always Christ in the East, only in the W God the Father will sometimes be shown in this way. Withal, in many contexts the person of the Trinity intended cannot be confirmed from the prototype lone, except in those images, like the Baptism of Christ, where Jesus the Incarnate Christ is also present, where the paw is clearly that of God the Father. After Eastern Orthodox images often identify Hands as the Logos with the usual monogram used in icons.[b]

Sometime Testament imagery [edit]

- In the Vienna Genesis the paw appears above the Expulsion of Adam and Eve from Paradise. More often, God was shown in this story using the conventional depiction of Jesus representing the pre-real Christ or Logos, who was seen as the Creator past Early Christian writers,[c] The story of Adam and Eve was the Old Attestation subject field most frequently seen in Christian art that needed a pictorial representation of God. A well known modern variant of the traditional hand motif is a sculpture of 1898 by Auguste Rodin called the Hand of God, which shows a gigantic hand creating Adam and Eve.

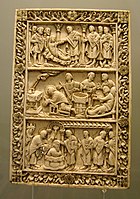

- The Sacrifice of Isaac first appears in Christian art in 4th century depictions from the Roman catacombs and sarcophagi, as well as pieces similar a fragment from a marble tabular array from Cyprus.[16] Abraham is restrained by the hand, which in the Sarcophagus of Junius Bassus grasped his pocketknife paw, every bit the angel frequently does in other depictions.[d] Notwithstanding the affections mentioned in the biblical text is more usual, and oft included as well. The apply of the manus in this scene, at to the lowest degree in Christian fine art, indicates God'south credence of the sacrifice, too every bit his intervention to alter it.

- Some depictions accept the hand passing Moses the Tablets of the Law, found in the Roman catacombs, various Bibles (come across gallery), the Paris Psalter, and in mosaic in the Basilica of San Vitale, Ravenna.[17]

- The prophet Ezekiel (2:9–x) received his prophecy by hand: "Then I looked, and I saw a hand stretched out to me. In it was a scroll, which he unrolled before me. On both sides of it were written words of complaining and mourning and woe"[18] and this and other moments from Ezekiel sometimes include the manus. In the Paris Psalter, Moses, Jonah and Isaiah are all shown blessed by easily, from which rays of light come. Other prophets are sometimes as well shown with the hand.

- In the Klosterneuburg Altar, Drogo Sacramentary (shown beneath) and San Vitale, Ravenna, Melchizedek is shown blessed by information technology, in the last combined with Abel. This relates to the approval of his sacrifice mentioned in the biblical text, and possibly also to the hand's association with divinely ordained monarchy (see below), as Melchizedek was both priest and male monarch co-ordinate to Genesis 14:eighteen–20, and his advent in art is often to evoke this every bit well as his function as a blazon for Christ.

- The hand tin can appear in other contexts; the Carolingian Utrecht Psalter atypically illustrates nearly all the Psalms, probably following an Antique model, and shows the hand in at least 27 of these images, despite besides using a figure of Christ-as-God in the heavens fifty-fifty more oft.[19]

- A mosaic in the Mausoleum of Galla Placidia in Ravenna shows the battle of Beth-horon with the Amorites (Joshua, 10:11), where: "Equally they fled before Israel on the road down from Beth Horon to Azekah, the LORD hurled big hailstones down on them from the heaven, and more of them died from the hailstones than were killed past the swords of the Israelites" – with a big manus representing God.

- The story in Daniel 5:1–31 of the writing on the wall is rarely depicted until the 17th century, when Rembrandt's well known version and others were produced.

-

Moses receives the Tablets, c. 840

-

New Testament imagery [edit]

- In depictions of the Life of Christ, the hand often appears at the Baptism of Christ representing the vocalism of God, in a higher place the dove representing the Holy Spirit, which is much more mutual, thus showing the whole Trinity as nowadays and active.[20] The mitt never seems to announced without the dove, as the Holy Spirit every bit a dove is mentioned in the Gospel of Mark: "As soon as Jesus was baptized, he went upwardly out of the water. At that moment heaven was opened, and he saw the Spirit of God descending like a dove and lighting on him. And a vocalization from heaven said, "This is my Son, whom I love; with him I am well pleased."[21] Both dove and manus are normally located centrally, pointing straight down at Jesus. The hand is generally constitute in Baptismdue south betwixt the sixth (due east.k. Rabbula Gospels) and 11th centuries.

- The hand is found in some Western and afterwards Armenian scenes of the Transfiguration of Jesus,[22] where once more the Synoptic Gospels have the vocalization of God speaking, this fourth dimension from a cloud.[23]

- The hand is sometimes seen in the Desperation in the Garden, though an angel is more than mutual. This is the 3rd and terminal occasion when the voice of God is mentioned in the gospels, this time only in the Gospel of John (12:28). The earliest known instance is in the St Augustine Gospels of c.600.[24]

- From Carolingian fine art until the Romanesque flow, the hand may announced in a higher place the peak of the cross in the Crucifixion of Jesus, pointing directly downwards. Sometimes it holds a wreath over Christ's head, as on the rear of the Ottonian Lothair Cross at Aachen Cathedral. The hand represents divine approval, and specifically credence of his sacrifice,[25] and possibly also the tempest mentioned in the gospels.

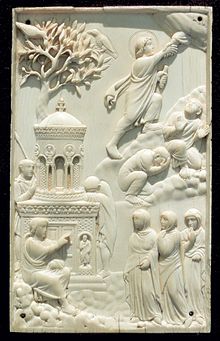

- The hand may be seen in the Ascension of Christ, sometimes, as in the Drogo Sacramentary, reaching down and clasping that of Christ, as though to pull him up into the clouds. The ivory plaque now in Munich (left) with such a delineation is possibly the earliest representation of the Rising to survive.

- In Eastern Orthodox icons of the Final Judgement, the hand often holds the scales in which souls are weighed (in the Westward Saint Michael typically does this). The hand may emerge from the Hetoimasia normally present, and is typically huge in size compared to the full figures nearby in the composition.

-

-

Hand with halo in 13th century stained glass of the Agony in the Garden

Divine blessing of rulers imagery [edit]

The manus often blesses rulers from above, specially in Carolingian and Ottonian works, and coins. The hand may agree a wreath or crown over the ruler'south head, or place it on the head. A posthumous money of Constantine the Great (the "deification issue") had shown the manus reaching down to pull upwardly a veiled figure of Constantine in a quadriga, in a famously mixed bulletin that combined pagan conventions, where an eagle drew deified emperors up to the heavens, with Christian iconography. From the tardily fourth century coins of Late Antique rulers such as Arcadius (and his empress), Galla Placidia and others show them being crowned past it – it was in fact more often than not used for empresses, and ofttimes only appears on issues from the Eastern Empire.[26] This theme is not then seen in Byzantine fine art until the late 10th century, when it appears in coins of John I Tzimisces (969–976), long after it was common in the W.[27] In later Byzantine miniatures figures the hand is often replaced by a full effigy of Christ (in these examples much smaller than the Emperor) placing a crown on the caput.[28]

A similar symbolism was represented past the "Main de Justice" ("Hand of Justice"), function of the traditional French Coronation Regalia, which was a sceptre in the grade of a short aureate rod surmounted by an ivory hand in the approving gesture. The object now in the Louvre is a recreation, made for Napoleon or a restored Bourbon king, of the original, which was destroyed in the French Revolution, although the original ivory hand has survived (now displayed separately). Engraved gems are used for an authentic medieval experience. Here the hand represents the justice-dispensing power of God equally being literally in the easily of the king.

-

-

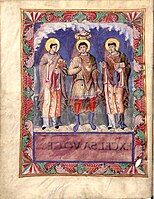

Charlemagne, flanked by two popes, is crowned, manuscript of c. 870.

-

Byzantine gold histamenon coin of 1041/ii. The emperor is crowned by the paw.

Saints imagery [edit]

The hand can also exist shown with images of saints, either actioning a miracle associated with a saint – in Cosmic theology it is God who performs all miracles – or to a higher place an iconic scene. In the Bayeux Tapestry the hand appears over Westminster Abbey in the scene showing the funeral of Edward the Confessor. The paw sometimes appears (see gallery) in scenes of the murder of martyrs like St Thomas Becket, clearly indicating neither interest nor approval of the human action, only blessing of the saint. In the dedication miniature shown, the blessing hand seems pointed neither at Emperor Henry 3, nor St Gregory or the abbot, but at the re-create of Gregory's book – the same copy that contains this miniature. This looser usage of the motif reaches its acme in Romanesque fine art, where it occasionally appears in all sorts of contexts – indicating the "right" speaker in a miniature of a disputation, or as the only decoration at the summit of a monastic charter. A number of Anglo-Saxon coins of Edward the Elder and Æthelred the Unready has a large hand dominating their reverse sides, although religious symbols were rarely then prominent on Anglo-Saxon coins.[29]

Icons [edit]

In Eastern Orthodox icons the paw remained in use far longer than in the Western church, and is still found in modern icons, commonly emerging from round bands. Apart from the narrative scenes mentioned above it is especially oftentimes establish in icons of military saints, and in some Russian icons is identified by the usual inscription as belonging to Jesus Christ. In other versions of the same composition a pocket-size figure of Christ of about the same size as the hand takes its place, which is too seen in many Western works from about 1000 onwards.

The earliest surviving icon of the Virgin Mary, of virtually 600 from Saint Catherine'southward Monastery, has an often overlooked paw, suggesting to Robin Cormack that the accent of the field of study is on the Incarnation rather than a simple Virgin and Child.[due east] Some other of the very few major Eastern works showing the Virgin from before the Byzantine iconoclasm, an apse mosaic (lost in 1922) from Nicaea, also shows the mitt above a standing Virgin. Few like uses of the hand are seen in later Virgins, though the iconographically adventurous Byzantine Chludov Psalter (9th century) has a small miniature showing the paw and pigeon above a Virgin & Child.[30] The hand occasionally appears in Western Annunciations, even as tardily as Simone Martini in the 14th century, past which time the dove, sometimes accompanied by a pocket-size image of God the Father, has go more common.[31]

Bearding print on the situation of the Netherlands in the 1570s, with iii hands

Ravenna mosaics [edit]

The mitt appears at the top of a number of Late Antique apse mosaics in Rome and Ravenna, above a variety of compositions that feature either Christ or the cross,[f] some covered by the regular contexts mentioned above, but others not. The motif is then repeated in much later mosaics from the 12th century.

Late Medieval and early Renaissance art [edit]

From the 14th century, and earlier in some contexts, full figures of God the Father became increasingly common in Western art, though yet controversial and rare in the Orthodox earth. Naturally such figures all have easily, which utilize the blessing and other gestures in a variety of ways. It may be noted that the well-nigh famous of all such uses, Michelangelo's creating hand of God in the Sistine Chapel ceiling, breaks clear of God's encircling robe above the wrist, and is shown confronting a plain background in a way reminiscent of many examples of the earlier motif.

The motif did not disappear in later iconography, and enjoyed a revival in the 15th century as the range of religious subjects greatly expanded and depiction of God the Begetter became controversial over again amid Protestants. The prints of Daniel Hopfer and others make frequent use of the hand in a diverseness of contexts, and the personal keepsake of John Calvin was a centre held in the Hand. Very gratis apply of the motif is made in prints relating to the religious and political fall-out of the Reformation over the next two centuries, in prints on the Dutch Revolt for example. In a high Rococo setting at the Windberg Abbey, Lower Bavaria, the Hand of God holds scales in which a lily stem indicating Saint Catherine's purity outweighs the crown and sceptre of worldly pomp.

The like but essentially unrelated arm-reliquary was a popular form during the medieval period when the hand was most used. Typically these are in precious metal, showing the hand and most of the forearm, pointing up erect from a apartment base of operations where the arm stopped. They independent relics, usually from that part of the body of the saint, and it was the saint's hand that was represented.

-

Miracle from the life of Saint Remy, c. 870, in the middle annals. Annotation the dove delivering the Sainte Ampoule at bottom.

-

The paw receives the souls of three martyrs born up to sky past Angels. Ávila

Examples in late antique and medieval Jewish fine art [edit]

The hand of God appears in several examples from the modest surviving body of figurative Jewish religious art. It is peculiarly prominent in the wall paintings of the third-century Dura Europos synagogue, and also seen in the nave mosaic of the sixth century Beth Alpha synagogue, and on a 6th-seventh century bimah screen establish at the quaternary-fifth century Susiya synagogue.[32]

Dura Europos synagogue [edit]

In the Dura Europos synagogue, the manus of God appears ten times, in five out of the twenty-nine biblically themed wall paintings including the Binding of Isaac, Moses and the Burning Bush-league, Exodus and Crossing of the Cherry-red Body of water, Elijah Reviving the Child of the Widow of Zarepheth, and Ezekiel in the Valley of Dry Bones.[33] In several examples the manus includes the forearm besides.

Beth Alpha synagogue [edit]

In the Beth Alpha synagogue, the paw of God appears on the Binding of Isaac console on the northern entryway of the synagogue's nave mosaic flooring.[34] The hand of God appearing in the Beth Alpha Bounden of Isaac mosaic panel is depicted as a disembodied manus emerging from a fiery ball of smoke, "directing the drama and its outcome" according to Meyer Schapiro.[35] The hand of God is positioned strategically in the upper center of the composition, straight above the ram that the affections of God instructs Abraham to cede in place of Isaac.

Susiya synagogue [edit]

In the Susiya synagogue, the paw of God appears on the defaced remains of a marble bimah screen that perhaps in one case illustrated a biblical scene such as Moses Receiving the Constabulary or the Binding of Isaac.[36] Though the hand was subjected to intense iconoclastic hacking, the iconoclasts left some vestiges of the pollex and the receding fingers intact.[37] A thumbnail has been carved into the thumb. Foerster asserts that the paw of God originally held a Torah scroll, identifying the minor piece of raised marble located betwixt the thumb and fingers as a Torah scroll.[38]

Birds' Head Haggadah [edit]

The hand of God appears in the early 14th-century Haggadah, the Birds' Head Haggadah, produced in Germany.[39] 2 hands of God appear underneath the text of the Dayenu vocal, dispensing the manna from heaven. The Birds' Head Haggadah is a particularly of import visual source from the medieval menses, as information technology is the earliest surviving example of a medieval illuminated Hebrew Haggadah.

Come across also [edit]

- Manus of God – other uses

- God the Father in Western art

- Finger of God (Biblical phrase)

- Sabazios

- Act of God

Notes [edit]

- Footnotes

- ^ A matter disputed by some scholars

- ^ For example in this icon, as compared to this i, which shows the Hand replaced with a Christ/Logos.

- ^ The account in Genesis naturally credits the Creation to the unmarried figure of God, in Christian terms, God the Father. Nonetheless the first person plural in Genesis 1:26 "And God said, Permit united states make man in our image, after our likeness", and New Attestation references to Christ as creator (John 1:3, Colossians 1:15) led Early on Christian writers to associate the Cosmos with the Logos.

- ^ Though both hand and knife are now missing, with simply a wrist stump at present remaining.

- ^ Meet also the alcove mosaic of the Euphrasian Basilica, from about the 550s, which has a very similar limerick.

- ^ One previously at Santi Cosma e Damiano (for example, encounter Dodwell, p. 5), seems now to have been restored away. Others are in Santa Cecilia in Trastevere, Santa Prassede, and others illustrated here.

- Citations

- ^ a b c "Anthropomorphism", Jewish Virtual Library, especially the section on Jewish fine art almost the cease.

- ^ Bar Ilan, 321–35; Roth, 191; C. W. Griffith and David Paulsen, 97–118; Jensen, 120–21; Paulsen, 105–16; Jill Joshowitz, The Hand of God:The Anthropomorphic God of Late Antiquarian Judaism: Archaeological and Textual Perspectives, (B.A. thesis, Yeshiva University, 2013).

- ^ Hachlili, pp. 144–145

- ^ Summarized by Hachlili, 145

- ^ Hachlili, 146

- ^ "in Ravenna and in Western fine art from the 9th until the eleventh centuries" according to Schiller I, 149, although Western examples of the hand in depictions of these occasions extend well before and after these dates.

- ^ Schiller, II 674 (Index headings)

- ^ For an overview of scholarship on anthropomorphism in biblical and rabbinic Judaism come across Meir Bar Ilan, "The Hand of God: A Chapter in Rabbinic Anthropomorphism", in Rashi 1040–1990 Hommage a Ephraim E. Urbach ed. Gabrielle Sed Rajna. (1993): 321–35; Edmond Cherbonnier, "The Logic of Biblical Anthropomorphism", Harvard Theological Review 55.iii (1962): 187–206; Alon Goshen Gottstein, "The Body as Image of God In Rabbinic Literature", Harvard Theological Review 87.2 (1994): 171–95; Jacob Neusner, The Incarnation of God (Philadelphia: Fortress, 1988); Morton Smith, "On the Shape of God and Humanity of Gentiles", in Organized religion in Antiquity ed. Jacob Neusner (Leiden: Brill, 1968), 315–26; David Stern, "Imitatio Hominis: Anthropomorphism and the Character(s) of God in Rabbinic Literature", Prooftexts 12.2 (1992): 151– 74.

- ^ Mark sixteen:nineteen, Luke 22:69, Matthew 22:44 and 26:64, Acts 2:34 and 7:55, ane Peter 3:22

- ^ "in Ravenna and in Western art from the ninth until the eleventh centuries" according to Schiller I, 149, although Western examples of the hand in depictions of these occasions extend well before and after these dates.

- ^ Linda and Peter Murray, "Trinity", in The Oxford Companion to Christian Art and Architecture (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998), 544.

- ^ C. Due west. Griffith and David Paulsen, "Augustine and the Corporeality of God", Harvard Theological Review 95.1 (2002): 97–118; Robin Jensen, Face to Face up: Portraits of the Divine in Early on Christianity (Minneapolis: Fortress, 2005), 120–21; David Paulsen, "Early on Christian Conventionalities in a Corporeal Deity: Origen and Augustine as Reluctant Witnesses", Harvard Theological Review, 83.ii (1990): 105–16.

- ^ Schiller, Ii 674 (Index headings)

- ^ Didron, I, 201–3

- ^ See index of Schiller 2 nether "Manus of God"

- ^ Weitzmann, Kurt, ed., Age of spirituality : late antique and early Christian art, third to seventh century, no. 380, 1979, Metropolitan Museum of Fine art, New York, ISBN 978-0-87099-179-0; full text available online from The Metropolitan Museum of Art Libraries.

- ^ Noga-Banai, Galit. The Trophies of the Martyrs: An Art Historical Report of Early Christian Silver Reliquaries, Oxford Academy Press, 2008, ISBN 0-19-921774-2, ISBN 978-0-xix-921774-8 Google books

- ^ Ezekiel Ch. 2, NIV

- ^ Utrecht Psalter online – for hands encounter Psalms ii,5,fourteen,21–23,26,29,xl,42,48,53–55,63,77,83,86,105,111,118,123–125,132,136–7.

- ^ Grabar, 115 & Schiller, I pp. 134 & 137–ix

- ^ Mark 3:16–17 NIV; all three Synoptic Gospels have the vocalism.

- ^ Schiller, I pp. 148–151. Encounter also Mathews, p. 96

- ^ Bible texts and commentaries

- ^ Schiller, 2, 49

- ^ Schiller, Ii, 107–108 and passim

- ^ Catalogue of belatedly Roman coins in the Dumbarton Oaks Drove and in the Whittemore Collection: from Arcadius and Honorius to the accretion of Anastasius, Philip Grierson, Melinda Mays, Dumbarton Oaks, 1992, ISBN 0-88402-193-9, ISBN 978-0-88402-193-3 Google books gives a full account of Belatedly Antique usage. Meet also David Sear coin glossary

- ^ Zach Margulies, "Christian Themes in Byzantine Coinage, 307 - 1204"

- ^ Examples here and here

- ^ Casson, 274 & illustration on 269

- ^ Schiller, I, p. seven & fig. three

- ^ Schiller, I pp. 43,44,45,47, figs 82, 97, 108

- ^ Cecil Roth, "Anthropomorphism, Jewish Art", in Encyclopedia Judaica, ed. Fred Skolnik and Michael Berenbaum (Thomson Gale; Detroit : Macmillan Reference USA, 2007), 191

- ^ Kraeling, 57

- ^ Eleazar Sukenik, The Synagogue at Beth Alpha, 40.

- ^ Shapiro, thirty

- ^ Steven Werlin, "Khirbet Susiya" in The Tardily Ancient Synagogues of Southern Palestine, (Ph.D. diss., University of Due north Carolina Chapel Colina, 2012): 525.

- ^ Steven Fine, "Iconoclasm: Who Defeated this Jewish Fine art", Bible Review (2000): 32-43; Robert Shick, "Iconoclasm", in The Christian Communities of Palestine from Byzantine to Islamic Rule: A Historical and Archaeological Study (Darwin Press Inc.: Princeton, North.J.), 213.

- ^ Foerster, Decorated Marble Chancel Screens, 1820.

- ^ "Bird's Head Haggadah", Israel Museum Digital Catalogue, State of israel Museum, Jerusalem http://world wide web.english language.imjnet.org.il/popup?c0=13475 Archived 2015-05-27 at the Wayback Machine.

References [edit]

- Bar Ilan, Meir. "The Paw of God: A Chapter in Rabbinic Anthropomorphism", in Rashi 1040–1990 Hommage a Ephraim E. Urbach ed. Gabrielle Sed Rajna. (1993): 321–35.

- Beckwith, John. Early Medieval Art: Carolingian, Ottonian, Romanesque, Thames & Hudson, 1964 (rev. 1969), ISBN 0-500-20019-X

- Cahn, Walter, Romanesque Bible Illumination, Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Printing, 1982, ISBN 0-8014-1446-6

- Didron, Adolphe Napoléon, "Christian Iconography: Or, The History of Christian Art in the Middle Ages", translated past Ellen J. Millington, 1851, H. G. Bohn, Digitized for Google Books.

- Casson, Stanley, "Byzantium and Anglo-Saxon Sculpture-I", The Burlington Magazine, Vol. 61, No. 357 (December., 1932), pp. 265–269+272-274, JSTOR

- Cherbonnier, Edmond. "The Logic of Biblical Anthropomorphism", Harvard Theological Review 55.3 (1962): 187–206.

- Cohen, Martin Samuel. Shi'ur Qomah: Texts and Recensions (Tübingen : J. C. B. Mohr (Paul Siebeck), 1985.

- Dodwell, C. R.; The Pictorial arts of the West, 800–1200, 1993, Yale UP, ISBN 0-300-06493-4

- Foerster, Gideon. "Decorated Marble Chancel Screens in Sixth Century Synagogues in Palestine and their Relation to Christian Art and Architecture", in Actes du XIe congrès international d'archéologie chrétienne vol. I–II (Lyon, Vienne, Grenoble, Genève, August 21–28 September 1986; Rome: École Française de Rome, 1989): 1809–1820.

- Goshen Gottstein, Alon. "The Body as Prototype of God In Rabbinic Literature", Harvard Theological Review 87.2 (1994): 171–195.

- Grabar, André; Christian iconography: a written report of its origins, Taylor & Francis, 1968, ISBN 0-7100-0605-5, ISBN 978-0-7100-0605-9 Google books

- Griffith, C. Westward. and David Paulsen. "Augustine and the Amount of God", Harvard Theological Review 95.ane (2002): 97-118.

- Hachlili, Rachel. Ancient Jewish Art and Archaeology in the Diaspora, Role one, BRILL, 1998, ISBN 90-04-10878-5, ISBN 978-90-04-10878-3, Google books

- Kessler, Edward in Sawyer, John F. A. The Blackwell companion to the Bible and culture, Wiley-Blackwell, 2006, ISBN ane-4051-0136-9, ISBN 978-1-4051-0136-3 Google books

- Kraeling, Carl H., The Synagogue: The Excavations of Dura Europos, Final Report VIII (New York: Ktav Publishing House, 1979)

- Jensen, Robin. Confront to Face: Portraits of the Divine in Early Christianity (Minneapolis: Fortress, 2005).

- Kraeling, Carl. The Synagogue: The Excavations of Dura Europos, Final Report 8, (New York: Ktav Publishing House, 1979).

- Lieber, Laura S. Yannai on Genesis: An Invitation to Piyyut (Cincinnati: Hebrew Union College Press, 2010).

- Mathews, Thomas F. & Sanjian, Avedis Krikor. Armenian gospel iconography: the tradition of the Glajor Gospel, Volume 29 of Dumbarton Oaks studies, Dumbarton Oaks, 1991, ISBN 0-88402-183-1, ISBN 978-0-88402-183-iv.

- Murray, Linda and Peter. "Trinity", in The Oxford Companion to Christian Art and Architecture (Oxford: Oxford Academy Press, 1998).

- Neusner, Jacob. The Incarnation of God (Philadelphia: Fortress, 1988).

- Paulsen, David. "Early Christian Belief in a Corporeal Deity: Origen and Augustine as Reluctant Witnesses", Harvard Theological Review, 83.2 (1990): 105–sixteen.

- Rabinowitz, Zvi Meir. Mahzor Yannai (Jerusalem: Bialik Institute, 1985).

- Roth, Cecil. "Anthropomorphism, Jewish Fine art", in Encyclopedia Judaica, ed. Fred Skolnik and Michael Berenbaum (Thomson Gale; Detroit : Macmillan Reference USA, 2007), 191.

- Schapiro, Meyer, Selected Papers, volume three, Late Antique, Early Christian and Mediaeval Fine art, 1980, Chatto & Windus, London, ISBN 0-7011-2514-4

- Schiller, Gertrud, Iconography of Christian Fine art, Vols. I & II, 1971/1972 (English trans from High german), Lund Humphries, London, ISBN 0-85331-270-ii I & ISBN 0-85331-324-five II

- Stern, David. "Imitatio Hominis: Anthropomorphism and the Character(due south) of God in Rabbinic Literature", Prooftexts 12.2 (1992): 151–174.

- Sukenik, Eleazar. The Aboriginal Synagogue at Beth Alpha: an account of the excavations conducted on behalf of the Hebrew University, Jerusalem (Piscataway, N.J.: Georgias Press, 2007).

mitchellspeausell.blogspot.com

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hand_of_God_(art)

0 Response to "Christian Symbolism Hand and Finger Gestures in Religious Art"

Post a Comment